This page aims to document the early dress and equipage of the regiment of Staffordshire Yeomanry, originally known as the Staffordshire Volunteer Cavalry. (It deals only with the county regiment; for a briefer treatment of Staffordshire’s independent yeomanry, volunteer and association cavalry units of this era – Bilston, Handsworth, Needwood, Pottery, Stone, Tamworth, Uttoxeter, Walsall, Wolverhampton – see this page.)

Full coverage is from formation in 1794 to the new uniform of 1826. Changes during the following decade plus are mentioned briefly at the end; at some point an extension to this page might cover them in more detail. Basic organisational history is briefly summarised in the opening section below.

Published sources (Webster, Benson Freeman, Smith and Coogan) only take us so far in this early period; a lack of reliable visual evidence means that some key aspects of dress remain vague. This is partly offset by detailed archival evidence, though that makes the treatment here massively long and wordy. For a simpler picture, I’ve included a brief “summary” of key points from the evidence at the start of each chronological section. Because the many references are a bit fiddly, evidence in the text is mostly footnoted to a numbered list of sources (archival, newspapers, publications etc) at the end.

Like other yeomanry corps, for whom no external regulations were prescribed, the Staffordshire regiment followed the practice of regular cavalry –in this case, light dragoons – but at a distance, and with major deviations. Changes of regular trouser colours are not imitated, the distinctive light dragoon double trouser stripes are not in evidence and in fact the light dragoon uniform of 1812 is bypassed completely.

The picture presented here deviates from received wisdom in two aspects: the original facing colour, and the new uniform of 1816. I’m fairly confident in my judgements on these, but it’s all a bit messy and forensic, and if I’ve created any errors here, I apologise.

Click to enlarge images.

* * *

Organisation

The organisational history of the regiment is covered by Webster [24] and Freeman [19], and is helpfully summarised for this earlier period by David J Knight [20].

The regiment of 1794 was commanded by Col George, Earl Gower, commissioned on 20 September that year. On 21 March 1800 Gower retired, the Hon Edward Monckton being promoted to Colonel. In late 1829, in his 86th year, Monckton resigned and Edward J Littleton, as Lieut Col Comm, succeeded to the command. He resigned in 1833, and was succeeded by Lieut Col Comm Thomas W Anson, Earl of Lichfield.

The original regiment comprised five troops: Newcastle, Stafford, Lichfield, Walsall and Leek. In 1800 a sixth troop was raised at Weston, and in 1803 another at Teddesley; the same year the independent Pottery troop was incorporated, making eight troops in all. In 1805 the independent Bilston (or Sandwell) troop was added to the regiment, while in 1806 the Newcastle and Pottery troops were disbanded, leaving seven: Stafford, Lichfield, Walsall, Leek, Weston, Teddesley, and Bilston. (In May 1805 it was reported that the Walsall troop was to be disbanded due to non-attendance, but this seems to have been avoided [17].)

In 1814 the independent Tamworth troop joined the regiment, though the other independent troops declined this option and disbanded. In 1817 a new Newcastle and Pottery troop was raised, and in 1819 three new troops were added, at Uttoxeter and Blithfield, Himley and Enville, and Burton, now making twelve troops in total. In late 1826, 1827 and late 1829 respectively, the Bilston aka Sandwell troop, the Weston troop and the Leek troop, all now reduced to small numbers, were disbanded, leaving an establishment of eight: Stafford, Lichfield, Walsall, Teddesley (from 1832 known as the Wolverhampton troop), Tamworth, Uttoxeter and Blithfield, Himley and Enville, and Burton.

First uniform: 1794-97

Other ranks: Tarleton helmet, white or silver metal, other details uncertain, but without a badge. Red or scarlet open jacket, yellow collar, cuffs and turnbacks, white metal or silver buttons in pairs. White waistcoat. White breeches. White shoulder sword belt, white waist (pouch) belt, probably black pouch. Cloak.

Officers: as other ranks, helmet with silver metal. Scarlet jacket faced pale yellow in superfine cloth, silver buttons, silver epaulettes. Crimson sash. Possibly cocked hat and coat for formal dress. White and/or black belts.

* * *

Following Webster’s regimental history of 1870 [24], the consensus was that the uniforms of 1794 to 1808 were faced in yellow. More recently this has been challenged by W Y Carman, and after him by Smith and Coogan [23], on these bases: first, that the source for Webster’s coloured illustration showing yellow was Eliot’s uncoloured image of 1797 (see below), second, that there is no actual documentation of yellow before Willson’s chart of 1806 [25], and finally that an uncoloured mezzotint of Sir Nigel Bowyer Gresley (see below), shows a collar dark enough to be black. It’s true that a few of the county’s independent troops, including the Loyal Pottery Volunteer Cavalry of 1798, adopted black facings (see this page). Even so, archival information, while sparse, does indicate that this regiment’s facings for the early period were described at the time as yellow (or sometimes “buff”) in line with those of the county’s militia (for whom, see this page). This seems to be confirmed by surviving regimental standards (see below). So my contention is that facings were a shade of yellow, maybe a pale shade, from the start.

A regimental committee meeting of 8 August 1794 [2] resolved:

That the following articles be provided …

A Coat and Waistcoat

Alike for Officers & Yeomen; the colour and form to be left to the Colonel of the Corps.

A Hat with Bearskin, Feather and Cockade

Alike for Officers & Yeomen, save that the feathers in the hat shall be varied so as to distinguish the Officers from the rest of the Corps

A pair of leather breeches

A pair of boots, spurs & spur-leathers. A bridle, a pair of stirrups, stirrup leathers, girths & a goatskin covering for the saddle

That cloaks be deferred for further consideration … according to patterns to be produced.

The next meeting, on 15 September [10], examined pattern items and approved them, with this exception:

That Helmets according to the pattern produced be provided for the Persons enrolling themselves in this Corps, instead of Hats as by a former Order.

Letters to Major Francis Percival Eliot [13] shed light on some of the details, Col Lord Gower writing on 22 September:

Mr Barber has declined sending down a foreman but he has undertaken to furnish the Cloth & also the superfine scarlet & buff for the Officers & he will give his plan of the Coat & Jacket to any of the Officers Taylors who may be in town & mine may serve for a pattern for the Taylors who live in the County.

Gower modelled the jacket at a meeting on 19 November [13], though it’s not clear whether his reference to “Coat & Jacket” means the jacket and waistcoat as worn, or an intended dress coat (see below). Suppliers were listed in accounts later published in the newspapers [15]: Thomas Barber for cloth for jackets and waistcoats; Burgess for helmets; Webb & Collins for cloaks; Woolley for epaulettes; Boulton & Scale [Birmingham] for buttons; Boulton & Smith for “belthooks“; Stephen Barber for stirrups, spurs, clasps, pads, surcingles etc; Bradnock for stirrups, girths, bridles etc; Ketlands & Co for pistols. During October and November 1794 some of these items became the focus of furious dispute among the committee, in which some privates resented officers’ distinctions; this “cavilling about trifles” provoked bitter accusations of levelling and republicanism. William Tennant, captain of the Walsall Troop, wrote to Eliot [13]:

The spurs, spur leathers, field epaulets, stirrups and stirrup leathers, girths & surcingles will, I hope, reach you in the course of the ensuing week; & in a little more than a fortnight, your proportion of Pistols will also wait on you. That G-d may send their contents into the heart of every democrat existing is the sincerest wish of Dear Sir, Yr’s Truly, Wm. Tennant.

In late November Eliot, impatient of “democratic” committee resolutions, wrote to Col Lord Gower and offered his resignation [13]:

I am well convinc’d that those who would wish to degrade and vilify the bearers of his Majesty’s commission, want nothing but the power to attack the throne itself. I have said before my Lord that it is not the form of an epaulette or the gilding of an ornament to the helmet, which gives me a moment’s concern, it is not the particular question, it is the general principle which I resist – so far from it that I should be very glad to have the common field helmet to save my better one for the evening, as I find that the Light Dragoon Officers in general have almost totally laid aside long coats & cock’d hats …

I even said that I thought Officers ought to be distinguish’d in the whole of their dress, & that tho’ I was perfectly contented to wear the same uniform as the private gentlemen I was well convinc’d that those who objected to whatever distinction the Officers chose among themselves to put on did not mean to serve their Country … they [his troop] ask’d me if it was not Shaw the schoolmaster who was at the bottom of it & that they were well aware of his character as a known enemy to the King & Constitution …

The Serpent is no longer contented with creeping in the grass, but is beginning to rear his crest & dart his venom abroad – we were told that the giving up the first question of the superfine cloth would suffice & that nothing further would be ask’d – to this succeeded the bridles then the epaulettes – the sashes were next attacked & now the helmets – & vires acquirit eundo [it gathers strength as it goes].

Besides their political interest, these remarks indicate that the intention had been for officers to wear uniforms of superfine cloth, sashes, epaulettes, superior quality helmets with some element of “gilding”, and, for formal or evening occasions, cocked hats and long coats – conceivably the “coat”, as distinct from the jacket, mentioned above by Gower. Though the levellers on the committee seem to have been in the ascendant at this point, it seems that in the event some of these distinctions were maintained. (I have not been able to identify “Shaw the schoolmaster”.)

The other ranks’ uniform of 1794 is shown in the frontispiece engraving (above), after a drawing by Major Eliot, in his Six Letters … of 1797 [18]. The helmet has a feather plume of darkish tone, a lighter turban, and a reinforcing strip of metal at the right, without any badge. The single breasted jacket is cut to fall open at the front, with non-functioning buttons, presumably at both sides, set in pairs as for the Staffordshire Militia; accurately or not, four pairs seem to be indicated. The plain collar (apparently falling), cuffs and single turnback are hatched in a mid tone, but are not black; the near cuff shows buttons in pairs. The turnbackmay have a button at the point, and there are buttons at the rear waist, apparently one at the top of each pleat below the shoulder seams. The waistcoat and breeches, with three buttons at the knee, appear white. A shoulder belt for the sword appears light in tone, possibly with a breast plate, and a small (black?) pouch is worn at the front on a waist belt. The rolled cloak is darkish in tone, the pistol holsters have fur covers, and the horse furniture is edged with two lines of pale lace, with a corner ornament of some sort of quatrefoil – or perhaps a crowned Royal cypher?

- Webster’s reprise of Eliot, as an ‘officer’

- Simkin

- Norie

A plate in Webster’s history of 1870 [24] reprises Eliot’s image as “An officer in review order” (though no sash or epaulettes are shown) and adds colours from unknown sources (pale or primrose yellow facings, white over red feather, black turban, silver buttons etc) on some of which we must reserve judgement. This is followed by other versions, notably in a watercolour of 1897 by Richard Simkin, online in the Anne S K Brown Collection, and in a rather fanciful painting of 1890 by Orlando Norie at the Staffordshire Yeomanry Museum, Stafford; Simkin throws in a helmet badge (wrongly) and double turnbacks for good measure.

A helmet that seems appropriate for this general period has been offered by The Military Gentleman. Its bearskin is acknowledged as a replacement, the erroneous green turban clearly is also; the white plume is said to be original, which may or may not be so. The metal, including the side strips without badge as in Eliot’s image, is silver plated, with the title “STAFFORDSHIRE / YEOMANRY” on the front ribbons. The helmet has been given a leather guard at the rear.

A second period image to take into account at this point is the mezzotint mentioned above, by J R Smith after his pastel of Sir Nigel Bowyer Gresley, an officer from 1794 to 1803. This is uncoloured (I’ve not seen the pastel original) and undated, and is not entirely compatible with the Eliot image. The detail is very slight, but the jacket shows a pair of buttons; the collar is now standing, with a single button, and is in a dark tone – a feature I can’t explain. Epaulettes are worn, presumably in silver, though their details are sketchy; the other officer’s distinction is a sash. Here the sword belt is black, and an oval belt plate possibly shows a crown or Staffordshire knot; a second black belt, presumably for the pouch, is worn over the left shoulder. Though mention is made in 1801 of both black and white pouches – see below – I can find no other reference at this stage to black belts.

Carbines were purchased by the corps at the government allowance of twelve per troop, Gower writing to Eliot on 22 September 1794 [13]:

With respect to the Carbines, I understand at Stafford that it was agreed to receive the Government allowance for them & that I should settle at the next meeting … what we are to determine upon the subject of that sort of arm.

(Webster [24] dates the first issue of carbines to March 1804, referring presumably to an Ordnance issue.)

Controversy over the first uniform seems to have extended to the designs of the standards presented to the initial three squadrons, Gower writing to Eliot in September 1794 [13]:

I approve much of your idea respecting the Standards, the proper King’s Standard for the 1st Squadron & the motto pro Aris & focis for the rest. Ploughshares & Pitchforks are excellent & respectable things but they have certainly little to do with Standards, non bene conveniant[they would not suit well].

Nevertheless, the chaplain’s speech at the presentation expressed the sentiment “that on their standards may be marked the sources of tranquillity amid the symbols of War”, while the motto “Pro Aris et Focis” was indeed featured, as confirmed by Eliot [18]. On 23 October 1795 the three standards were presented to the Stafford, Newcastle and Lichfield troops by the Countess of Sutherland, wife of the Colonel [16]. The King’s standard would presumably have been crimson, while the two regimental standards were yellow. These were among those eventually retired and replaced in 1835, which were then given into the care of Lord Lichfield and later passed to John Brace of Lichfield, who in 1870 placed them with Lieut Col Lord Bagot at Blithfield Hall, where, among the neo-gothic tracery of the great hall, several of the squadron standards still hang.

Images currently available to me are hazy, but the standards appear to be yellow, presumably with silver fringe, with oval cartouches in each corner, the upper hoist and lower fly with the white horse of Hanover, the other two presumably with the title or initials of the corps. The central design appears to be a crowned Staffordshire knot within a wreath, above a ribbon presumably bearing the motto “Pro Aris et Focis”.

Second uniform: 1797–1800

All ranks: as before, but with closed jacket. White belts and pouch. White gloves. Sash for NCO’s. Undress (exercise days): helmet or round hat; previous jacket, or blue frock with red collar; miscellaneous pantaloons or overalls; no sash.

* * *

In April 1797 new jackets were adopted; since the orders below note that waistcoats would not be seen under these jackets, they must have been of a more up-to-date cut, closed at the front, presumably longer waisted than later jackets, in the manner of the light dragoon jackets of this date, and presumably with singly spaced buttons, though I’ve found no further details. They were replaced in 1800. The Regulations of March 1797 of the Colonel’s (Newcastle) Troop [7] require:

Hair to be dressed and clubbed. Jacket and waistcoat, until new jackets are used – afterwards any waistcoat that will not be seen under the jacket. Leather breeches, or breeches of same colour. Sword belt, gloves, pouch and pouch belt all white. Black spurs. If knee caps worn to keep breeches clean, these should be as near as possible the colour of the breeches.

Note that both belts and the pouch were currently white. Following the issue of the new jackets, a draft of rules and regulations for Eliot’s Lichfield troop of 21 April 1797 [13] prescribes a liberal variety of undress for days of exercise:

It is proper to observe that on the monthly field day, the whole troop will be required to appear in their best jackets, with clean white leather breeches; the Officers & non comd officers with their sashes; & the linking collar & goat skins on the horses of the whole – but on the intermediate days of exercise, the old jackets with pantaloons or overalls of any sort will be allow’d, the sashes, goatskins & collar will not be required, & such gentlemen as have not second jackets may appear, in blue frocks with red capes & regimental buttons, with the skirts hook’d back, & round hats – but on all days it is particularly required that every gentleman has his hair powder’d, & either tied in a queue, roll’d close & neat over a roller, or cut short in the neck, & by no means hanging loose.

Third uniform: 1800-08

Other ranks: helmet, possibly with red turban, white metal or silver badge, white over red plume. Scarlet jacket in superfine cloth, yellow superfine collar and cuffs, three rows of silver ball and half ball buttons apparently without lace, red or scarlet lace apparently on collar and cuffs. White breeches. Scarlet sleeved cloak with buff or yellow collar, and possibly cuffs. Waist sword belts. Watering dress: forage cap, probably blue stable jacket, probably white trousers, shoes.

Officers: helmet and jacket apparently as other ranks. White breeches. New pattern of sash. Waist sword belt. Second dress: blue pantaloons, Hessian boots.

* * *

Clothing and “appointments” were completely renewed in 1800, Gower receiving an allowance of £2412 from government for this in December 1799 [24]; clothing and accoutrements were reckoned at £14 9s 2d per man in September 1800 [1]. These are itemised in almost identical terms in several printed sets of troop regulations of this period [12]:

Regimental Jacket & helmet – the Hair to be dressed & queued – Black Stock or Handkerchief, the Ends not to appear – White Breeches, Gloves & Belts – Regimental Boots & Spurs – Pouch & Pouch Belt – Sword & Pistol in proper order, – Cloak, Cloak Case & all the Regimental Horse Furniture & Accoutrements, including Linking Collars.

As in 1797, no waistcoat is specified, showing that the jacket was closed. At this time the fashion would have been for a shorter, waist length cut. Cloth for jackets was purchased from Robert Wright of Stafford and tailored by the corps [1]. A costing in the Bridgeman papers [1] prices the men’s jacket at £2 7s 6½d, and shows that it was of officer’s quality superfine double milled scarlet cloth with collar and cuffs of superfine yellow broad cloth. A letter of 1800 from William Keen, Capt-Lieut of the Stafford troop from 28 March, to Adjutant Robert Mayne [4] confirms that the “lining” or facings of the new jackets were “the same as the old”, i.e. yellow. The Bridgeman document [1] specifies 2¾ yards of silk braid; no colour for this is given, but as Willson’s chart of 1806 [25] gives the officers’ lace as “red”, it may well have been scarlet. The costing calls for 26 “large” buttons and 54 “small”; while some of these may have been required for the cloak included in this document (see below), this suggests up to 26 large or ball buttons on the front opening, and 27 small or half ball on each outer row. But in any numbers approaching these, given just 2¾ yards of braid, these front rows of buttons cannot have been laced. A letter to Adjutant Mayne of 1804 from button makers Joseph Nutting of Covent Garden [11] suggests that jackets may have been renewed in 1803.

The Bridgeman costing [1] also includes a sleeved cloak, made of 4½ yards of 6/4 milled scarlet cloth and 1/8 yard of buff cloth – enough to face the collar, if not also the cuffs. The term “buff” here suggests that the yellow facings were still of a pale shade. The cloak was part lined with shalloon, presumably white, with a yard of separate lining for the sleeves. Regimental orders of 23 September 1801 [6] confirm that all troops were by then furnished with cloaks, which were to be “rolled and buckled over the holsters in proper marching order”.

Keen’s letter [4] gives some details of other items. The new helmets, ordered from Hawkes, showed “a considerable alteration” from the previous pattern. (A surviving helmet probably of a later date – see below, fourth uniform – has a red turban, a plate or badge on the right side, and a white over red plume, features perhaps introduced at this time. The badge is described as a crown over a garter enclosing the “GR” cypher over a Staffordshire knot.) Breeches were to be of white leather. A new pattern of officer’s sash was chosen by Col Monckton. Sword belts were to be altered by Hawkes, and some “cartridge” (pouch) belts also shortened by the same firm. Judging by a letter to Mayne from Thomas Hawkes [4], the existing shoulder sword belts were altered in March 1801 to make waist belts. New spurs were to be made locally at Walsall. New “tails” (queues) were provided.

A list of ordnance of 1800 for the new Weston troop [1] shows that single pistols were issued. A “Return of Arms & appointments in the stor[e] room” of the Lichfield troop of February 1801 [5] lists, among other items, carbines and bayonets, pistols, black pouches, white pouches, sword belts, goatskins, cloaks and cloak straps. Cloak cases were in use by 1803. The troop regulations mentioned above [12] specify that horses were to be “brought well trimmed” with “Tails cut short in the Military mode”.

Other developments of the next few years included, in January 1804, the introduction of an undress or “watering dress” of forage cap, stable jacket (almost certainly blue) and trousers (probably white), and for officers the use of blue pantaloons and hussar (Hessian) boots as a second dress. A copy at the Regimental Museum of printed Regimental Orders of 15 September 1805 defines orders of dress which include these items:

FIELD-DAY ORDER, MOUNTED

Regimental Jacket, Helmet and feather, Arms and Accoutrements. Cloak in the Case, Head Collars.

WATERING ORDER

Stable Jacket, Trowsers, Shoes, and Forage Cap.

CHURCH, OR DRESS, FOOT PARADE

Regimental Jacket, Helmet and Feather, Leather Breaches, Boots and Spurs, Sword and Belt.

UNDRESS, FOOT PARADE

Stable Jacket, Trousers, Forage Cap, and Shoes, no Arms, unless ordered for Drill.

OFFICERS

On Evening foot parades, Officers to be in Blue Pantaloons, Hussar Boots and Spurs.

On Morning foot parades, in Leather Breaches, Boots and Spurs, Swords to be worn on all occasions.

Details can be added from regimental orders, many in the Adjutant’s Orderly Book of 1804-15 [3, 9]:

20 January 1804 (marching order): Neatly folded under the Cloak Case a Horse Cloth … The cloak to be rolled 40 Inches long and strapped over the Holsters.

Beside the above articles, which it is presumed every Yeoman is already possessed of, there are others which, as some of the Troops have furnished themselves with, and others may follow the example, it is proper that they should be of a Regimental pattern. One of each sort will therefore be sent to the Troops, that in case the Men choose to provide themselves with, at their own expence, they may be uniform.

Prices

12 9 A Stable Jacket, To be folded and strapped on in the Cloak

6 7 Trowsers,

4 0 Watering Cap,

2 6 Feeding Bag, Fasten’d to the Cantle of the Saddle, off side

4 0 Havresack, Slung over the men’s shoulders

1 6 Canteen,

Officers are not to carry their Cloaks over the Holsters, but in the Cloak Case, unless ordered otherwise.

27 January 1804: In order that the men may appear clean on the Evening Parade the Captains will as well to recommend strongly that they provide themselves with stable dresses, and of these Trowsers are certainly the most necessary part. For officers: After evening parade blue pantaloons and Hussar boots may be worn.

19 February 1804: A Foot Parade tomorrow Evening in the Market Place at 4 o’clock. The men to be in their watering dresses without arms. Those who are not furnished with them will parade in their red Jackets & Helmets.

21 February 1804: Officers may appear in pantaloons and hussar boots on the parade this Evening.

11 September 1804 (afternoon foot parade): The men to appear in their Stable Jackets, Trousers and Forage Caps and without arms.

27 September 1804 (inspection): The men will be in the following order. In full regimentals, the Cloak worn in front, and their Cloak Cases well packed with their necessaries, but without Horse Cloths, Canteens, Havre Sacks, or nose bags.

6 June 1805: Officers to appear in blue pantaloons and Hussar boots with spurs fastened to them on Evening Parades, except the Officer of the day, who is at all times to be in full uniform.

19 June 1805: The Men to be in Field Day order. Viz: Regimental Jacket Helmet Feather Arms (except Carbines) and Accoutrements. The Cloaks in the Cases …

22 June 1805 (morning foot parade): The officers and men to be in full Regimentals, Boots & Spurs, and Swords. But without pouch belts.

Regimental orders [3, 9] of January and February 1804 and June 1805 show that four standards were now in use, one for each of four squadrons, but that standards were not taken out on field days, camp colours being used instead, one per squadron or troop.

Fourth uniform 1808-16

Other ranks: new helmet, with red or possibly black turban, white over red plume, badge. Dark blue jacket, white collar and cuffs, three rows of silver ball and half ball buttons apparently with white lace, white lace also probably on collar and cuffs. White breeches. Cloak. Sash for sergeants. White belts. White gloves. Watering dress: forage cap, probably blue stable jacket, probably white trousers, shoes.

Farriers’ jacket as privates, white cloth horse shoe on right sleeve. Trumpeters’ jacket probably white faced blue, with blue or white lace.

Officers: “regimental” jacket, dark blue superfine cloth, trim possibly as men’s. Dress jacket with silver lace. Plain white “regimental” waistcoat. White dress waistcoat with white braid trim. White breeches. Dark blue pantaloons, with blue silk French and figuring braids, with Hessian boots. Dark blue overalls, strapped with the same, with chains, and sometimes with leather cuffs. Dark blue great coat, with blue olives, blue cord, blue French and figuring braids. White belts. Black dress sword belt.

* * *

In 1808 the uniform was radically revised. Again, no contemporary visual evidence survives for this, but Regimental Orders of March 1808 [3] outline the basics:

The Uniform to be blue with white facings. The Regiment will be furnished with new Jackets, Cloaks, Helmets & Feathers, Bridles, Breast Plates, Cruppers and Pads, and such new Flounces for the Holsters as may be absolutely wanted. The Serjeants will also be supplied with proper sashes.

Cloth and Trimmings for the Jackets and Cloaks, with Lace, and Buttons, will be sent to the Captains of Troops for their non-commissioned officers and private gentlemen.

The Helmets and feathers will be supplied by Hawkes & Co Piccadilly, and those now in wear of the Regiment are to be returned to them in the Packages in which the new ones are sent. And the Captains of Troops are requested to send the whole of the Helmets they may have in their possession of the present Uniform … A pattern Jacket and Cloak will be sent to each Troop, and the Captains are desired to pay the most particular attention that no deviation be made therefrom. The Tailors should be instructed to overlay the seams of the Jackets so as to admit of enlargement or alteration.

… The Trumpeter’s Jackets will be made in London. The Farrier’s Jackets to be the same as the Privates with a Horseshoe of white cloth upon the right arm, and to insure uniformity in this article they will be made by one Tailor and sent to the Captains of Troops …

Officers

Pattern Jackets, Great Coats, Pantaloons overalls and white dress waistcoats are left for the Inspection of the Officers at Meyer & Meagoe’s No 25 Mortimer Street Cavendish Square. Pattern dress swords and Black Belts are to be seen at Hawkes & Co’s Piccadilly …

A Medical Staff uniform will shortly be fixed upon for the Regiment and the particulars will be made known to the Gentlemen of that department …

(The “Medical Staff” uniform is intriguing, but no further reference survives. Meyer’s seems to have been the favoured regimental tailor for many years, and will be mentioned again below.) The changeover was not complete in time for September’s permanent duty, which was postponed until Spring 1809.

Benson Freeman’s 1907 regimental history [19] adds a number of extra but unreferenced details here, possibly from regimental records, which must be noted, but with caution: white collar and cuffs with white lace; three rows of silver buttons in front, looped in white lace; the “backs” of the jackets (presumably the side seams) ornamented with white lace; the white leather breeches retained; the helmet with a black turban and white over red plume; white belts for all ranks; blue cloaks with white collars; officers’ lace silver; officers’ waist sashes of crimson. For musicians, see below. The silver buttons and officer’s lace are also mentioned by Webster [24]. The officers’ dress jacket was presumably similar to that detailed under the fifth uniform, below, as opposed to the officers’ “regimental” jacket for day to day wear, which was presumably similar to that of the men.

An invoice of March 1808 from button makers Joseph Nutting of Covent Garden [11] is for 17 gross (2,448) of solid silver plated ball buttons, 37 gross (5,328) of “breast” or half ball, and 727 yards of lace (presumably white). Clearly the ball buttons are for the centre row, closing the jacket front, and the “breast” or half ball for the outer, ornamental rows. A confident reconstruction is not possible here, but a troop of 100 men would have had enough buttons here for three rows of 20 or more, with ten “breast” buttons left over for a stable jacket and 7¼ yards of lace per man, though this length of lace appears quite insufficient for the purpose.

This also confirms that the men’s jackets used silvered buttons. These may well have been of the type recorded by Ripley and Darmanin [21] as 204 – silver, “domed”, with the incised design of a Staffordshire knot, recorded in a diameter of 17 mm. (No earlier pattern has yet been identified.)

also confirms that the men’s jackets used silvered buttons. These may well have been of the type recorded by Ripley and Darmanin [21] as 204 – silver, “domed”, with the incised design of a Staffordshire knot, recorded in a diameter of 17 mm. (No earlier pattern has yet been identified.)

Items tailored or supplied for officers during this period are noted in a ledger used by the London tailor Jonathan Meyer from 1809 onwards [14], which survives at the successor firm of Meyer & Mortimer. In May 1814 Major Littleton purchased a “dress Suit Staffordshire yeomanry” at the very considerable price of £43 11s 9d; this would have included a dress jacket, ornately laced in silver, as discussed under the fifth uniform, below.

The officer’s dark blue “regimental” jacket may well have been of a pattern similar to that of the men. Those made by Meyer for Capt Edward Nicholls of the Stafford Troop are in superfine cloth with calico or silk lining. Waistcoats are noted as of fine white Marcella (piqué) cotton trimmed with (white) cotton braid (Nicholls – presumably a dress waistcoat), or of white cassimere (Major Edward Littleton, 1814). Breeches are noted in white cassimere (Littleton). Dark blue pantaloons are of superfine cloth (Nicholls) or six thread stocking (Cornet John Mott, Teddesley troop, 1811), both ornamented to a regimental pattern with blue silk French braid and figuring braid. Dark blue overalls are of superfine cloth (Nicholls) strapped with the same (reinforced on the inside leg), or of blue second cloth (Mott), strapped with the same and with leather cuffs; both types have chains under the foot. (A pair of milled cassimere overalls and a pair of white duck cossack trousers are noted for Lieut Edward Monckton Jr of the Bilston troop in 1814 and 1815, assuming that these are military items.)

The regimental pattern of great coat mentioned in the Orders of 1808, above, is recorded by Meyer in 1809 as of dark blue second milled drab cloth, with 33 blue silk “Olaves” on the front, so possibly single breasted with three rows of up to 11 olives. Ornamentation, including, we can assume, looping between the three rows, is in blue Royal cord, with at least an equal quantity of blue figuring braid, probably largely on edges, and a smaller length of blue French braid, perhaps on collars and cuffs; each coat appears to use about 25 yards of cord, more of figuring, and five yards of French braid. The sleeves are lined in black silk. (One completed coat was purchased by Nicholls, while trim for three coats was sent to a Mr Talkington, probably the tailor for the Lichfield troop.)

Smith and Coogan [23] describe a helmet, sold in 1988, that may be an officer’s of this period or perhaps later. (See also the helmet discussed above under first and second uniforms.) This has a red turban and white over red feather plume, with a badge on the right side of a crowned garter enclosing a “GR” cypher above a Staffordshire knot. It also has chin scales, suggesting a slightly later period.

A few more details of officers’ dress of 1808-09 can be found in the Bridgeman papers [1]: among items ordered from Hawkes are a “regimental” sabre, a “dress” sabre, a black Spanish leather waist belt, and “An Hussards Silk Sash”, meaning the type with narrow tasselled tails, rather than a barrel sash. For horse furniture, Cornet Bridgeman purchased from Gibson and Peat a blue cloth shabraque bound with blue silk lace and tassels, with a white review collar and a pair of blue girths. The style of the shabraque seems relatively modest.

A printed Orders of Parade of 27 May 1809 [3, also contained in 9] provides orders of dress:

Marching Order

… To be folded in the Horse cloth and carried over the Cloak Case

Stable Jacket, Trowsers, Forage Caps, a pair of shoes, a Snaffle Bridle

… The men in Regimental Jackets, Helmets & Feathers cased, white Leathern Breeches, Boots and spurs, white gloves, Horse Collar, Arms and Accoutrements.

Watering Order

Stable Jacket, Trowsers, shoes and Forage cap …

Church or dress foot Parade

Regimental Jacket, Helmet & Feather uncased, Leathern Breeches, Boots and spurs, Sword and Belt.

Undress Foot Parade

Stable Jacket, Trowsers, Forage Cap, and shoes.

Officers

On evening Foot Parade, Officers to be in blue Pantaloons, Hussar Boots and spurs, Dress Swords and black belts. Regimental White Waistcoats; the Jackets to be worn open and the sashes under them.

At all other times they will appear in blue Overalls and the Jackets closely buttoned. Leather Breeches not to be worn, but when orders are particularly given for that purpose.

New details here include the blue overalls for officers, and the casing of helmet feathers. Again, regimental orders [3] help to amplify the picture:

2 June 1809: It has been observed that the horse cloths of the regiment are not uniform, and as it is very desirable that they should be so; I am desired to beg that you will request of your Troop to supply themselves with common stripped [striped] rugs, such as are in general use. They are of the proper size for packing the Stable dresses.

11 June 1809: The Regiment will Parade tomorrow morning at 10 o’clock on foot in Watering Dresses, Helmets, and Swords, for foot drill.

12 June 1809 (morning mounted parade, for drill): The Men in Stable Jackets, boots spurs Helmets & feathers cased, swords & Cartridge Belts.

17 June 1809 (church parade): The Men in full Regimental Jacket, Leather Breeches, boots & spurs, & swords. No Cartridge belts. The Officers to be dressed in blue pantaloons, Hussar boots & spurs. Jackets buttoned close & sashes over them. Dress swords & belts. The feathers of the regiment uncased.

19 June 1809 (inspection): Officers will be dressed tomorrow in overalls … The feathers of the Regiment to be uncased.

29 May 1811 (review): The men to be in full Regimentals review order, the Cloaks (without cases) folded behind, and the feathers uncased. Officers in blue overalls, full Regimentals …

- Simkin’s officer

- Simkin’s private and trumpeter

At this point we need to note in passing three figures dated 1808 from a multi-figure watercolour of 1897 by Richard Simkin. (This is online at the Anne S K Brown collection.) These clearly rely on Webster, and must be taken as visualisations of existing evidence with some speculative details, such as the form of the cuff, rather than as reliable primary sources. For example, I see no reason why the officer’s pantaloons should be shown in a lighter shade than his jacket. They show an officer, a private and a trumpeter.

For trumpeters, a regimental order of 11 June 1810 [3] states:

The Captains are also desired to order their Trumpeters to practice, and make themselves masters of the Trumpet and Bugle duty … It is also expected that the Trumpeters be well mounted on Grey Horses …”

Webster [24] and Freeman [19] record that a regimental band was organised in 1809 at the expense of the officers, and was present at the permanent duty of June that year.

As mentioned above, the trumpeters’ jackets were not tailored by the regiment but made in London, so must have been more ornately laced. Freeman [19] gives, without any source, the trumpeters and bandsmen in white jackets faced and laced in blue. However, in two pages of notes in the R J Smith folder [22] by an unidentified writer (but possibly Lionel E Buckell) the reference to blue lace has been crossed through. On the Simkin watercolour (see above) the lace is shown as white.

Fifth & sixth uniforms 1816-26

Other ranks: helmet as before, probably with red turban, white over red plume, badge, and with chin scales by 1824. Dark blue jacket, white collar, cuffs and lace, possibly single breasted with three rows of buttons without loops. Grey pantaloons/overalls, white seam stripes. From 1823, dark blue pantaloons/overalls, white seam stripes. Cloak. Sash for sergeants. White gloves. Watering dress: forage cap, probably dark blue with white band and button, stable jacket, white duck trousers, shoes.

Officers: helmet as before, probably with red turban, white over red plume, badge, and with chin scales by 1824. Dark blue dress jacket, probably with white collar and cuffs, three rows of silver ball and half ball buttons, edged, ornamented and looped with silver lace. “Regimental” jacket probably as men’s. White “regimental” waistcoat. Dark blue dress trousers with silver lace seam stripe. Dark blue pantaloons, presumably with blue silk braids, with Hessian boots. Grey undress trousers with white seam stripe. From 1823, dark blue undress trousers, white seam stripes. By 1824, also white trousers. Dark blue forage cap with silver band and button, possibly with black peak. Sash. Black patent leather waist belt, black leather dress waist and pouch belts, all with silver plated furniture.

* * *

At this point confusion is prompted by Webster’s [24] statement that in 1816 clothing and equipment were “entirely re-organized … and the uniform entirely renewed”, but that “Much the same style was maintained”, featuring “A blue dress jacket, with white facings, and but little lace”. Freeman [19] amplifies this on some unidentified basis as “A double-breasted blue coatee, faced, collars and cuffs, and turned up with white, the officers’ collars and cuffs being laced with silver and silver epaulettes instead of scales …”, though he apparently contradicts himself by stating that the “chief alteration in the uniform” was the introduction of overalls.

The general assumption seems to be that Webster’s “jacket” involved a full move to the 1812 light dragoon uniform, but there is unlikely on several counts: firstly, a tailor’s note of 1817 (see below) shows that the officer’s dress jacket, at least, was then still in the old single breasted light dragoon style with loops; secondly, mention of a double breasted “tailed jacket” is crossed out in the anonymous notes, mentioned above, in the Smith folder [22]; thirdly, all sources agree that the Tarleton helmet was long retained (in fact until 1831), but a new style light dragoon outfit would logically have required a cap. For that matter, it would also have required “waterfall” fringe at the rear waist and an 1812 pattern girdle, but the first mention of either of these is with the new uniform of 1826 (see below).

- Simkin’s fantasy for 1816

- Norie’s fantasy for 1810

- Norie’s fantasy for 1816

Nevertheless, the Freeman theory found a ready visualisation in the Simkin watercolour of 1897 mentioned above, where the figure for 1816 wears a full 1812 light dragoon outfit, complete with ornate sabretache and shabraque, sitting oddly with the Tarleton helmet. More worryingly, the watercolour of 1890 by Orlando Norie at the regimental museum shows figures for 1810 and 1816 in a version of the crested “Austrian” helmet of 1812, and an 1812 “heavy” dragoon jacket with white laced front edges. Though these are obvious misinterpretations, I believe the Simkin light dragoon image should also be discounted.

So what pattern of dress jacket was actually adopted? Webster’s brief description of “much the same style” suggests a dark blue single breasted jacket without skirts, with white collar and cuffs and three rows of buttons. His “but little lace” suggests no front loops. Adjutant Mayne’s notes (below) specify less than nine yards of lace (presumably white) per jacket – insufficient to loop the buttons, but enough to ornament collar and cuffs, edges and back seams. (The absence of front looping recalls the jacket of 1800-08.) Such a jacket would be compatible with the cut of the officer’s dress jacket discussed below.

Freeman [19] gives new “blue green” Wellington trousers or overalls with double white cloth seam stripes. Other sources, below, make it clear that these were “mixed” or grey, and that those of officers, at least, had single, not double seam stripes. In fact, I’ve found no evidence that double stripes were ever adopted for any rank. By this point the terms “pantaloons”, “overalls” and “trousers” seem to be used pretty much interchangeably.

Freeman [19] mentions the introduction at this point of “undress soft muffin shape round forage caps of dark blue cloth with white band and button”, meaning a white cloth “button” on the crown. Unless this is Freeman’s calculation of what should have been “regulation” at this time, it seems specific enough to be convincing, despite being unsourced.

A letter of 26 January 1817 to Adjutant Mayne from Cornet R Wood of the Uttoxeter troop [4] shows that, as before, cloth, buttons and trimmings were supplied to troops, for their tailors to make up dress jackets, stable jackets and pantaloons. Leek troop tailor’s accounts for 1819-22 [in t] show that the tailors made up and trimmed the men’s dress and undress jackets, and dress and undress (Russia Duck) pantaloons, made cases for the helmet feathers, and altered some forage caps supplied by military clothiers.

A “List of Appointments &c Furnished to the Staffordshire Yeomanry” drawn up by Adjutant Mayne on 1 February 1820 is included among regimental orders [9], and itemises the full kit:

Three Cloak Straps 1s/7d. Two Valise do 1/6.

Helmets, Feathers & Cases; Spurs, Stirrup Irons; Pouches & Belts; Forage Caps; Valises; Sheep Skins & Straps; Serjeants Sashes; are made by contract and will be sent to the Troops.

Clothing

Dress Jacket Cloth 1½ yd per each Jacket. Buttons and Lace supplied. This quantity of lace will Average under 9 Yds per Jacket. Allowed for making 8s. For trimmings Lining &c of every kind found by the Tailor} 15/- each.

Undress Jackets Narrow Cloth 2½ ys each, and Buttons supplied.

Allowed for making 5 “ 6

For trimmings [??] 3

Cotton Cas’d[?] “ 10

9s 4d ea

Gray Pantaloons. Cloth 2½ Yds each and facings supplied. Allowed for making lining Buttons & trimmings found by the Tailor} 9d a pair

Cloak Cloth 4½ yds each; lining 3½ yds ea & Buttons supplied

Allowed for making & trimmings of every sort 9s each

Russia Duck Pantaloons Made complete to Pattern Allowed per pair 12s

Sword, Pistols, Sword belts & knots are supplied from the Ordnance Stores & will be forwarded to the Troops. The Yeomen find their own Boots, Saddle & Gloves.

A printed Orders of Parade of 8 April 1817 [in 22] revises the equivalent 1809 orders (above) appropriately for the new uniform:

MARCHING ORDER

Stable Jacket at one end of the Valise … Russia Duck trowsers in the middle … Forage Cap … The Cloak to be rolled forty Inches long, and strapped over the Holsters – the Sheep Skin over all.

The Men in Dress Regimental Jackets, Helmets and Feathers cased, grey Pantaloons, Boots and Spurs, white Gloves, Arms, and Accoutrements.

WATERING ORDER

Stable Jacket, Russia Duck Trowsers, Shoes and Forage Cap …

DRESS FOOT PARADE

Regimental Jacket, Helmet and Feather uncased, grey Pantaloons, Boots and Spurs, Sword and Belts.

UNDRESS FOOT PARADE

Stable Jacket, Russia Duck Trowsers, Forage Cap, and Shoes.

This usefully confirms that undress or watering dress trousers were of white duck. A version updated to 1 March 1820 [in p] adds that white gloves were to be worn at Dress Foot Parade, and that “The Jacket to be close buttoned up on all Parades, and Duties, and no White to be shewn above the Handkerchief.”

Again, various regimental orders [9] help to give a fuller picture:

27 September 1818: To foot parade in Market place exactly at 5 o clock, the Men in stable dresses without arms …

2 Oct 1818 ( Inspection): The men to be in full Regimentals Helmets & feathers uncased the Cloaks & Sheepskins to be worn. The Black horse furniture without Cloak or Great Coat or valise is to be worn & White head horse Collars.

17 September 1820 (Drill): The men will be in undress Jackets, Helmets & Grey Pantaloons with Sheep Skins, Cloaks & Valises on the saddle.

22 Sept 1820 (Review): Full uniform … The Cloaks will be neatly folded & carried in front & the sheep skins worn without the valises … White horse collar to be worn & the feathers uncased …

Webster [24] and Freeman [19] note that in 1816 Col Monckton applied for the entire regiment to be equipped with carbines. What was received was a type used by “heavy” dragoons, fitted with a bayonet, which was found unsuitable and returned. A current light dragoon carbine was issued instead, but only to the previous allowance of twelve per troop.

Moving onto the complex question of officers’ dress, an order of 2 October 1818 [9] refers specifically to officers’ “Regimental (not Dress) Jackets” confirming that the “regimental” was a plainer version, modelled on that of the men, as noted for the fourth uniform, above.

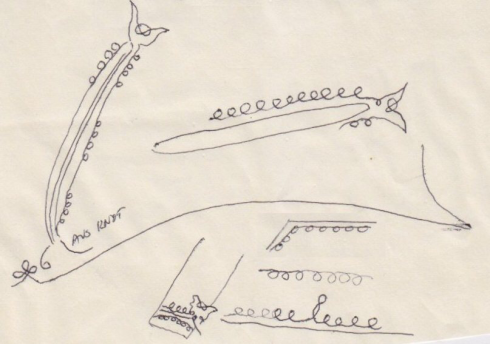

The Belcombe 1817 dress jacket: a rough sketch by or after Buckell, from Buckmaster’s sketch. Above, centre rear and right side seam, pocket and front lower point. Below, cuff, collar front and rear.

Evidence for the dress jacket is found in a letter of late August 1817, once owned by P W Reynolds, from Cornet H S Belcombe to Mr Buckmaster, the London tailor, on which Buckmaster has made notes and rough sketches of some details of the pattern dress uniform as obtained from Meyer’s. (A transcript and rough copy by Lionel E Buckell is in the Smith folder [22].) Details are obscure in places; it seems likely that the collar and cuffs are still white, though this is not mentioned in the notes. The dress jacket is single breasted with three rows of 22 buttons, with silver lace loops, terminating in a “crows’ foot” or trefoil at the top outer button. The silver plated buttons are “larger in front” and “smaller behind”, i.e. balls on the front row and half balls or “breast” on the outer rows. The edges are all laced in silver, the edging forming a trefoil at the centre rear waist. The cuffs are pointed, and the “pelisse” style sleeve has no back seam and no buttons behind. The skirt length is “small”, about two inches. The collar is edged with a row of continuous inward facing eyes, presumably in a finer silver figuring braid, but the lower line forming a single double eye at the rear centre. The pockets at the sides are edged likewise, and at each pocket end the braid forms a “winged” Staffordshire knot. Each side seam appears to be overlaid with lace, and edged with a continuous line of finer braid that forms three sets of four eyes on each side, terminating in a “winged” Staffordshire knot at the top, and a single curl and an Austrian knot (“Aus knot” in the sketch) at the base. The cuff is edged round the base with a row of braid eyes facing down; the top appears to be edged with a line of braid with a single eye at the point, while above this is another line of eyes facing upwards, with a “winged” Staffordshire knot above the point. The pockets are lined with silk and leather.

A quantity of silver lace was despatched by Meyer [14] to a George Stevens of Lichfield (presumably a tailor) in June 1818, perhaps indicating that this jacket was still current.

Also noted by Buckmaster are dark blue dress trousers with a 1½ inch silver lace seam stripe, and mixed (grey) second dress trousers with a 1½ inch white stripe.

Freeman [19] mentions the introduction at this point of “undress soft muffin shape round forage caps of dark blue cloth with … silver band and [silver] laced button with black dropping peak”. Again, this sounds convincing, though no source is given. (An early peaked officer’s cap of an unidentified date at the Regimental Museum is of a more rigid construction, and possibly later.) The Challinor and Shaw papers [8] list purchases of December 1816 from Hawkes of a “Reg[imenta]l forage cap w[it]h Silver trim[min]gs“.

Orders of dress are appended to the 1817 Orders of Parade [in 22] mentioned above:

OFFICERS

MARCHING ORDER

The Cloak or great Coat to be carried over the Holsters; a small Valise behind; and a Black Sheep Skin over all.

To be dressed in full Regimentals, Arms, and Accoutrements, the same as the Men.

On Evening Foot Parade, Officers to be dressed in blue Pantaloons, Hussar Boots and Brass Spurs, Dress Swords and Belts, Regimental white Waistcoats; the Jackets to be worn open, and the Sashes under them.

At all other times they will appear in grey Pantaloons, and the Jackets closely buttoned.

A distinction is made between ordinary and dress swords and belts, though all belts appear to have been black. The blue pantaloons still worn with “hussar” or Hessian boots were presumably closer fitting than the grey pantaloons.

As with the men, regimental orders [9] help to give a fuller picture:

27 September 1818 (Drill): Officers in gray Pantaloons & Caps, Stripped Saddles but with holsters and Flounces. To foot parade in Market place exactly at 5 o clock … Officers in white trousers.

2 Oct 1818 ( Inspection): The Officers to be in Helmets and feathers, uncased, Regimental (not Dress) Jackets, Arms & Accoutrements & Grey Pantaloons.

As already noted, the distinction made here between “regimental” and “dress” jackets is significant.

17 September 1820 (Drill): Officers on stripped saddles & without shoulder Belts.

22 Sept 1820 (Review): The Officers will have Cloaks or Great Coats in front over the Holsters their Valises behind & the whole Covered with the Black Sheep Skins. White horse collar to be worn & the feathers uncased …

Side arms and accoutrements for this period are detailed in an account of December 1816 from Hawkes for officers of the Leek troop [8]:

Officers Mod[el] Field Sabre emboss[e]d blade & steel scabbard

Patent Leather waist [belt] w[it]h plated reg[ulatio]n fur[nitur]e

Steel Mod[el] Dress Sabre w[ith] scabb[ar]d

Bl[ac]k Spanish Leather Dress Waist Belt w[it]h plated fur[nitur]e

Hussar silk sash once ro[un]d … rich silk knots of bullion tassels

Reg[u]l[ation] Pouch w[it]h Spanish leather Belt Plated buckle tips slide &c

There is no sign of the laced dress belts worn by officers of regular light dragoons.

Regarding trumpeters, in his letter of 26 January 1817 to the Adjutant [4], mentioned above, Cornet Wood of the Uttoxeter troop asks for white cloth for two pairs of pantaloons. As the men’s pantaloons were now “mixture”, I can only think that these were for the trumpeter.

The next uniform was created by the introduction in late 1823 of new pantaloons in dark blue with white seam stripes, replacing the grey. Regimental orders of 25 August and 2 December [9] give a picture of the process:

… as ample time will now be given to make up the new Pantaloons the Coll requests that great care may be taken to have them uniformly made and properly fitted to the men. Particular instructions on this head will be sent with the cloth to the commanders of troops.

The cloth for the new pantaloons will be sent to the Troops immediately … A pattern pair will be sent to each troop. The quantity of cloth allowed is 1¼ yd of broad cloth and 2 nails of white for facings for each pair of pantaloons. For making and materials of every description the tailors will be allowed 6/6 a pair. The Officers pantaloons may be made with the Pidgeon hole cut at the top of the hindstep, the mens boots not being made high heeled will not admit of that form … Remember that the pantaloons are made long & wide enough.

A “nail” was 1/16 yard or 2¼ inches of cloth. On 18 December the Lichfield store issued, with the 50 yards of double blue cloth for the 40 men of the Leek troop, 5 yards of white for the stripes. Again, my conviction is that the seam stripes were single, not double, for all ranks.

A couple of orders [9] add a little more:

23 May 1824 (Drill): The men will be in undress Jackets blue pantaloons and Helmets. The sheepskins Cloaks and Valises not to be worn …

27 May 1824 (Drill): The men will be in Stable Jackets white trousers and watering Caps … (Inspection): .. to see that the Cloaks are neatly rolld the clasps[?] of the shoulder Belts well polished and the Buttons and the scales of the Helmets well clean[e]d.

This is the first reference I’ve seen to chin scales being added to the helmets, as on the surviving helmet mentioned above under the fourth uniform.

With regard to officers, the total of cloth issued by the regimental store to the Leek troop in late 1823 [9, see above] included 4 yards of blue for their pantaloons, so possibly of a superior quality. Orders of 1824 [9] add a couple of other details:

23 May 1824 (Drill): Officers with Strip[pe]d Saddles and without Shoulder belts.

27 May 1824 (Drill): Officers in white pantaloons and Caps Cas[e]d.

This is the first reference I’ve noted to officers’ undress caps being cased. Their white pantaloons or trousers may have been for summer wear.

Seventh, eighth & ninth uniforms 1826-38

In 1826 a new pattern of men’s dress jacket was introduced. This was, unusually, a single breasted version of the dark blue light dragoon jacket of the period, without lapels but with rear skirts, with a white collar, cuffs and turnbacks, a fringe “waterfall” at the rear waist, and shoulder scales. It was worn with a light dragoon “girdle”. The existing helmets, trousers, cloaks, stable jackets and duck trousers were retained. Sabretaches, apparently plain black,appear to have been introduced circa 1830.

The equivalent “regimental” jacket for officers was as the men’s, but of superior materials; the shoulder scales were replaced by epaulettes in 1834. In 1826 the existing officer’s dress uniform, as discussed above for 1816, was retained for the time being, but was eventually replaced by a single breasted tailed light dragoon jacket of the new “regimental” pattern, but with silver lace and braid heavily ornamenting the collar, cuffs and back seams. By 1836 the officer’s dark blue dress trousers had a 2¼ inch seam stripe in silver oak lace.

In 1831 the Tarleton helmet was at last replaced by the new pattern of shako introduced for regular light dragoons circa 1828-31, dark blue, six inches tall with a Maltese cross on the front. (Other sources give 1837 for this, but the evidence is clear.)

In 1838, with the acquisition of Royal status as the Queen’s Own Royal Staffordshire Yeomanry, the facings were changed to scarlet, and other minor alterations were made. The single breasted tailed light dragoon jacket was worn until 1859.

* * *

1 County Record Office D 1287/10/1 (O/148), F/487: Bridgeman/Bradford papers.

2 County Record Office D 1300: printed notice of committee meeting, 8 August 1794, also in Aris’s Birmingham Gazette, 25 August 1794.

3 County Record Office D 1300/1/1: Adjutant’s Orderly Book.

4 County Record Office D 1300/2/5.

5 County Record Office D 1300/6/1.

6 County Record Office D 1300/6/2.

7 County Record Office D(W)1788 p1 B5.

8 County Record Office D 3359/15/14/1: Challinor & Shaw papers.

9 County Record Office D 3359/60/10/1: Challinor & Shaw papers, notebook of Leek troop.

10 County Record Office D 6015/3/1: printed notice – “Staffordshire Volunteer Cavalry” meeting, 15 September 1794.

11 County Record Office D 6015/4/7.

12 Articles to be Observed by the WESTON TROOP, OF STAFFORDSHIRE YEOMANRY CAVALRY, 1800, in [1]; Trentham Troop of Staffordshire Volunteer Cavalry, 1800, and REGULATIONS for Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Edensor Heathcote’s Troop [Trentham] of Staffordshire Yeomanry Cavalry, 1803, in [4].

13 William Salt Library, Stafford, 5/49: Ms bundle, papers of Francis Percival Eliot.

14 Meyer ledger, Meyer & Mortimer, Savile Row. Images of pages courtesy of Ben Townsend.

15 Staffordshire Advertiser, 25 July, 1 August 1795.

16 Staffordshire Advertiser, 24 October, 21 November 1795. Derby Mercury, 29 October 1795.

17 Gloucester Journal, 27 May 1805.

18 Francis Percival Eliot, Six Letters on the Subject of the Armed Yeomanry, Addressed to the Rt Hon. Earl Gower Sutherland, Colonel of the Staffordshire Volunteer Cavalry …, London, 1797.

19 Benson F M Freeman, “Historical Records of the Yeomanry Regiments. No 22. The ‘Queen’s Own Royal Staffordshire Imperial Yeomanry’ “, Volunteer Service Gazette 2, 9, 16, 23 January 1907.

20 David J Knight, Directory of Yeomanry Cavalry 1794-1828, Military Historical Society Special Number 2013.

21 Howard Ripley & Denis Darmanin, Yeomanry Buttons 1830-2000, Military Historical Society Special Number 2005.

22 Robert J Smith, “Staffordshire 1795-1858”, research folder.

23 R J Smith & C R Coogan, The Uniforms of the British Yeomanry Force 1794-1914, 15: Staffordshire Yeomanry, Robert Ogilby Trust & Army Museums Ogilby Trust, 1993.

24 P C G Webster, The Records of the Queen’s Own Royal Regiment of Staffordshire Yeomanry, Lichfield & London, 1870.

25 James Willson, A View of the Volunteer Army of Great Britain in the Year 1806.