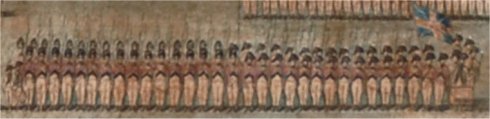

Since prestige confers publicity, the iconography of the great volunteer movement of 1794-1808 is very London-centric. This is true not only of the uniform prints and portraits of obscure colonels, but also of commemorative prints of reviews, among which Hyde Park predominates.

An exception is this coloured print of a painting by a Mr Hopkins (possibly William Hopkins, miniature painter) of the Grand Review of volunteers of West Yorkshire, held on Heath Common, Wakefield, in August 1796. In November 1798, almost two years after the event, an advert in the Leeds Intelligencer announced:

“GRAND REVIEW Of the GENTLEMEN VOLUNTEERS of Leeds, Wakefield, Halifax, Bradford, and Huddersfield, as commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Lloyd, and reviewed by Lieutenant-General Scott. MR. HOPKINS, Miniature-Painter, No. 27, King-street, Bloomsbury-square, London, begs to acquaint the Ladies and Gentlemen of the above-mentioned Places, and their Environs, that the PRINT of the GRAND REVIEW, from his PICTURE taken on the Spot, is now finished, and to be seen at Mr. Wright’s, Printer, and at Mr. Greenwood’s, Bookseller, Leeds; Mr. Meggitt’s and Mr. John Hurst’s, Booksellers, Wakefield; Mr. Brook’s. Huddersfield; and at Mr. Edward’s, Halifax; where Subscriptions are received.

The above Print contains several Hundred Figures, so richly coloured as to represent a Painting and the respective Corps in their full Uniforms; the Whole forming a grand and interesting Spectacle.”

The enterprising Mr Hopkins’ original painting may be lost, but a few prints survive. In 1976 I looked at the copy held by the Thoresby Society in Leeds, thickly varnished and a bit the worse for wear. Forty years on, this has been donated to Leeds Museum; despite conservation efforts, it has suffered further in the interval, but at least a nice big image is available online here.

- A drummer of the Leeds Volunteers

- Drummer, Major Commandant and light company man of the Royal Wakefield

Hopkins’ detached perspective means that the assembled ranks appear far smaller than the less interesting foreground figures, but there’s still plenty here to round out our otherwise patchy view of this 1794 generation of volunteers. From the left of the picture stand the Leeds, Bradford, Huddersfield, Royal Wakefield and Halifax Volunteers in that order, all in scarlet faced respectively with blue, buff, blue, blue and black. The Bradford and Halifax “battalion guns” (two brass six pounders in each case) hold the ends of the line, while the West Riding Yeomanry keep the field and chase away stray dogs and naughty boys.

The front ranks of the Halifax Volunteers – grenadiers at left, battalion company, band and regimental colour at right

The artillery detachments are in blue with round hats, while all the drummers except the Wakefield are in white. All in are short gaiters. The grenadier company of the Halifax are in fur caps, while all the light companies (at the viewer’s right of the rear echelons), and all ranks of the Huddersfield Fusiliers wear Tarleton helmets.

Not at the event (at too much of a distance, presumably) are the Loyal Independent Sheffield Volunteers, the Doncaster Volunteers, York Volunteers and Royal Knaresborough Foresters, all likewise raised in 1794.

Mr Hopkins’ advertisement doesn’t give a price for a copy of this grand and interesting Spectacle. These can’t have been cheap, though; the hand colouring must have been one heck of a chore.