The presence of black musicians in the British Army of the later 18th and early 19th centuries is well documented. The craze for “Turkish” or “Janissary” music brought percussion instruments into regimental bands – bass drum or kettledrum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, crescent or “Jingling Johnnie” – and black percussionists to play them, perhaps chosen for perceived exotic value as well as for percussive ability. Though band uniforms were already extravagant products of regimental vanity, these musicians were even further distinguished by their fantastical and pseudo-oriental costumes, often involving ornamented turbans and Turkish-style “shells”.

This rather interesting thesis outline notes that 41 line regiments of foot are known to have employed black musicians (the actual number was perhaps much higher), but observes that their novelty and visibility rather eclipsed the honourable record of ordinary black soldiers who served in the ranks, who were often overlooked in contemporary accounts and imagery.

Less widely recognised, perhaps, are the black musicians who served as frequently with the Militia, so here are a few examples. The watercolours by Captain Sir William Young of the Buckinghamshire Militia of 1793 include a “cymbalist” and a “tamborin”. (The originals, in the British Museum collection, are not available online, but copies are in the Anne S K Brown collection.)

A regimental order of June 1797 of the Staffordshire Militia required “Grenadiers, Light Infantry & Drummers [to parade] in their respective dress caps. Musick in jackets. The Blacks in their best Turbans.”

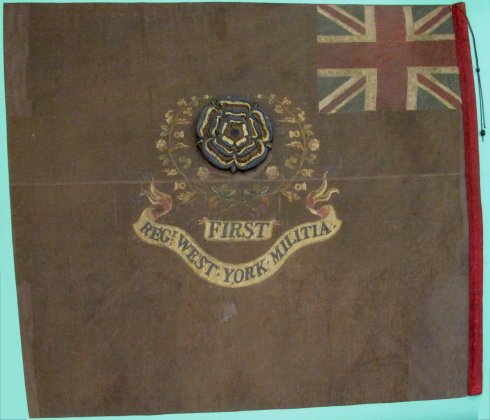

Service in a regimental band must have been an attractive option for those fallen on hard times. In November 1807 Adjutant Butterfield of the 1st West Yorkshire Militia wrote to his Colonel that “Major Dearden has this moment directed me to express his wish to have a Black, taken from the Prison here, as a Tamboreen in the Band to complete our number.”

That number might be as many as five percussionists. Among the clothing supplied to the Shropshire Militia for 1811 were five “Cymbol &c dress Jackets, Shells, Pantaloons and Waistcoats”; in 1813 the same five musicians were supplied with “Fancy Caps” with “Ornaments” and “long feathers”.

“Music jacket & Shell” for the North Gloucestershire Militia, 1796, from the Pearse tailor’s books, Canadian War Museum collection

A 1796 tailor’s drawing for the North Gloucestershire Militia gives some idea of the construction of such garments. One element of the many curious and fossilised features of military musicians’ dress of the era was a fringe around the elbow or wrist, and the drawing shows a scarlet long sleeved “waistcoat” (or jacket) worn under an open white “jacket” (or shell) with short, elbow length sleeves to which this fringe was attached.

There is some evidence that showier or better heeled volunteer regiments may also have employed black musicians. The print of John Hopkins’ painting of the 1796 “Grand Review of the Gentleman Volunteers” at Wakefield seems to indicate white turbaned percussionists among the bands of the Bradford, Leeds and Royal Wakefield Volunteers. A plate from Walker’s Costume of Yorkshire (1814) shows the Bishop Blaise procession in Bradford, held in 1804 and 1811. If the original sketch was made in 1804 the military in the procession would be the Bradford Volunteers. (If in 1811, their successors in the Morley Local Militia.) Prominent in the relatively small band are a black bass drummer and cymbal player, in red sleeveless shells over yellow jackets, yellow pantaloons, red fezzes and white turbans.

The movements of the cymbal player suggest that, in contrast to the formal composure of the brass and wind players, free expression was the norm. Period accounts of regular infantry bands mention black players’ “contortions and evolutions” – “throwing up a bass drum-stick into the air after the beat, and catching it with the other hand in time for the next, shaking the ‘Jingling Johnnie’ under their arms, over their heads, and even under their legs, and clashing the cymbals at every point they could reach.”