It’s usually a good idea to finish researching before posting, but my piece in June on that most mysterious of garments, the light dragoon pelisse of 1811, turns out to have been a bit lacking, so below is a new, expanded version, now with a new postscript and image added at the end on 30th August. (The original post is deleted.)

HRH Prinny’s scandalously Frenchified “plastron” uniform of late 1811 for the Light Dragoons is familiar from many images, and from surviving jackets. But here, from the Royal Collection, is something less familiar – a watercolour by Denis Dighton of a private of the 12th Light Dragoons with some sort of pelisse flying from his shoulder. [Click all images to enlarge.] The depiction is rather vague: dark blue, with a few white buttons and what looks like crimson fur lining and cuffs. Dighton squeezes the shape in awkwardly between cap cords, sabre, pouch and distant horizon, which I suppose might indicate a late addition to the painting. It’s all a bit odd. At the risk of attracting a heap of correcting emails, this is one of only two contemporary images of a light dragoon I know that show such a thing. But what exactly is it?

The ledger of tailor Jonathan Meyer contains entries for a number of pattern garments made for the Prince Regent in 1811. (My thanks to Meyer & Mortimer and to Ben Townsend for access to images of the pages.) For September 26 1811 an account is made for a pelisse, “pattern for Light Dragoons,” in superfine blue cloth, lapelled (i.e. double breasted) and of jacket size at 1½ yards of cloth. The body was lined with scarlet plush, the sleeves with scarlet silk, two dozen plated half ball buttons were used, the hips were fringed and necklines were attached. Side and sleeve seams, as on the more familiar jacket, were welted in scarlet cloth. While the Dighton image shows pelisses worn by privates, Meyer’s details indicate an officer’s garment, and the Board of Clothing was charged a whopping £8 12s for it.

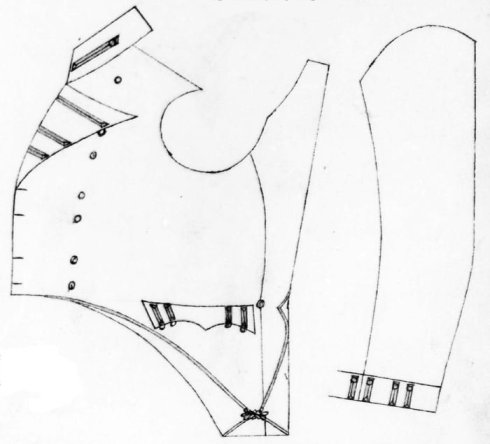

Remarkably, we have a tailor’s drawing of just such a pelisse as Meyer describes – if not the very same one – in William Stothard’s “Rigementals” book in the Anne S K Brown collection. It’s captioned “Pleece to the Princes Pattron [pattern]. 1813,” though that year seems to be the date of the drawing, not of the making of the garment. Again, Stothard’s entries are invariably of officer’s clothing. Though the nine button front is shown as if intended to be buttoned across, Stothard’s drawing shows the skirts, with fringe and pleats, entirely in the light dragoon style.

Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library

Shag (coarsely napped cloth in imitation of fur) or plush (finer and shorter napped) is shown on collar, cuffs, turnbacks and lapel facings; interestingly, the false pocket is also shown lined and/or edged with it. The double lines drawn on the side and sleeve seams confirm the piping in facing colour as mentioned by Meyer, though there is no sign of this in the Dighton image. The drawing does not show any necklines.

As we’ll see in a moment, the facings of the pelisse should have been in the regimental facing colour. Though the 12th had yellow, Dighton shows the pelisse faced in crimson, as if for the 9th or 23rd; red or scarlet as in the Meyer pelisse would suggest the 8th or 16th. It could be that Dighton was shown a pattern pelisse with crimson or red lining, and, taking that for a universal colour, put it into his image of a man of the 12th. In late 1811 the proposed men’s pelisse was clearly still enough of a live option for Dighton to include it in his documentation of the new uniform; in the event, along with some other enthusiasms of the Prince Regent, the idea was abandoned as too expensive or too impractical, and it was never issued.

But the pelisse was in general wear by officers; the General Order of December 1811 regulations authorised for officers “a short surtout … to be worn likewise as a pelisse on service.” Here are some examples:

The Meyer ledger also contains three orders for pelisses for officers of the 9th Light Dragoons, from 1811 and 1814. These are of superfine blue cloth with gold fringe and necklines, and one is noted as lined with crimson plush.

The Hawkes tailor’s book at the National Army Museum has a brief description of a pelisse of 1816 for the 11th Light Dragoons:

Short Pelesse of do [blue superfine cloth] to be lind with buff Shag Collar Cuffs lappels and turn backs Regl. Butts

Mollo and Haythornthwaite also cite Sir Thomas Reed’s recollection of officers of the 12th at Waterloo in blue cloth pelisses lined with yellow silk plush.

The Buckmaster tailor’s book at the National Army Museum has notes for a pelisse for an officer of the 14th, probably in 1814 (“strap” here meaning the top of the jacket lapel):

Pelisse same as Jacket, only no Point in centres of strap top facing, Lin’d & Facd with Orange shag

Lieut Col Luard of the 16th recalled:

… the officers were also instructed to wear a jacket called a pelisse, as an undress. It was very plain, double-breasted, without ornament of any kind, with a rough shaggy lining; the collar and cuffs of the same, and of the colour of the facings of the regiment. Certainly it was not brilliant in appearance, and there was nothing about it to denote the officer; indeed it was not so gay as the clothing of the private dragoon; but it was very comfortable, put on and off in an instant; and on the dreadfully wet night preceding the battle of Waterloo, was found to be a most serviceable jacket.

In 1813-14 officers of the Light Dragoons of the King’s German Legion [see page 10 of my KGL pages] bought from Meyer superfine blue regimental pelisses with gold fringe and necklines; the colours of the facings are not given.

Haythornthwaite’s version

Put together, all these examples confirm that the pelisse was cut exactly like the jacket apart from the form of the lapel tops, and that shag or plush was applied to the lining, lapels, collar and cuffs of the pelisse in the regimental facing colour. The mention in Meyer of a gold neckline for an officer of the 2nd KGL Light Dragoons, whose metal colour was silver, suggests that, like the light dragoon officer’s cap cords, the pelisse neckline may have been universally in gold.

As an afterthought, I’m left wondering why the 1811 officer’s pelisse is almost entirely missing not only from period images, but also from modern illustrations. There is, for instance, almost no sign of it in Carl Franklin’s pretty exhaustive compendium. It does show up, shorn of all detail and apparently with a white lining, in a Cassin-Scott figure taken from Dighton’s image of a man of the 12th in (I think) Philip Haythornthwaite’s Uniforms of Waterloo of 1986. The only remotely accurate portrayal appears in the Fostens’ The Thin Red Line of 1989, on an officer of the 13th in Plate XIII (see also below). This is copied wholesale (along with most of the rest of the plate) into the D Lordey page of light dragoons in the Quatuor Les Uniformes des Guerres Napoléoniennes of 1997 by Coppens, Courcelle, Lordey and Pétard. (Was this licensed? Or straight plagiarism?) More importantly, Lordey manages in the process also to alter the correct buff lining to white. Oh well. You can’t have everything …

The Thin Red Line original, and the Lordey copy with incorrect lining

Postscript

Langendijk’s original

And here, a bit late in the day, is the original source for the pelisse of the 13th, in a watercolour, apparently of an officer of that regiment, by Jan Anthonie Langendijk in the Royal Collection. (This has been published only in black and white.) The image shows the plush or shag facings well, though, oddly, it includes epaulettes and, below the rear fringe, old fashioned double turnbacks that look like a mistake, while the front lapels, as far as we can see them, appear to be of normal cloth. This pelisse is shown faced white with silver lace/metal; the “white” is an easy misapprehension for the actual pale buff of the 13th, but silver would be a definite error for the 13th’s gold.

Another Langendijk image in the Royal Collection, of an officer of the 2nd Light Dragoons of the King’s German Legion, also shows the pelisse in wear. The plush or shag collar and cuffs are clearly shown, but again, an epaulette is worn, while the lapels appear to be of cloth, and are worn like those of the jacket, buttoned back and closed as if with hooks and eyes.

The turnback problem may account for why the Fostens and Carl Franklin choose to show this from the front only. These two images may include some doubtful features, but they are still good contemporary evidence for the use of the light dragoon pelisse.